A Youth Caregiver Lights the Way for Acceptance, Awareness of PTSD

Month of the Military Child

Most 17-year-olds don’t have Kris Rotenberry’s keen awareness of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) triggers. Then again, most teenagers don’t have a U.S. Marine Corps dad who lived through combat in Iraq and Afghanistan.

That awareness was evident when Kris was first to notice his dad’s reaction after a balloon popped in the middle of a friend’s birthday party.

“It was already chaotic and loud,” Kris recalled. “I knew the whole night that he was going to be stressed. I saw my dad run to the bathroom. He threw up. He ran outside. I followed him out.”

A Marine veteran, and friend of Kris’ dad, also followed. Kris’ dad, Chuck Rotenberry, was able to count on their support as he verbalized how the balloon triggered flashbacks. It dragged him back downrange to the time an IED detonation immediately followed hours of fierce gun fighting.

“My dad saw his fellow Marine lose both legs, then they were ambushed and had to fight for hours,” Kris said. The now high school senior understood what his dad was going through, and how daily life can be a minefield of PTSD triggers. Kris was glad to be there for him.

Kris is insightful as he describes how people could interpret his dad’s reaction in different ways. He sees not only his dad’s perspective, but others’ as well. That gives him both a wisdom and a burden beyond his years.

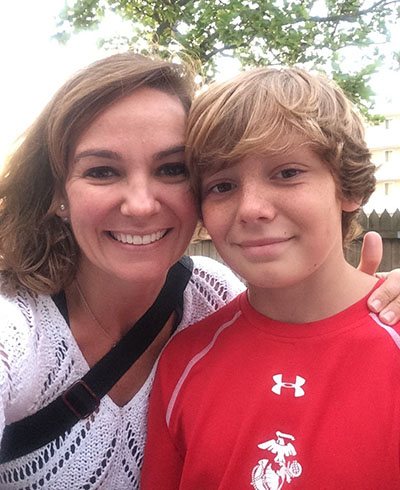

“Kris has taken on so much and has so much weight on his shoulders,” his mom, Liz, said. Liz left her original career to become her husband’s caregiver. She eventually became a caregiver advocate and the Dole Caregiver Fellows program manager, an Elizabeth Dole Foundation initiative that assists military families and veteran caregivers by providing support, training, and a platform to address the issues impacting the community.

Liz reminded Kris as he was growing up that she would prefer to have him play and “not worry about me and your dad and the house.” His dad feels guilty about the effects his combat stress and PTSD have had on Kris and his younger three siblings.

The parents have found support through veterans service organizations that surround the entire family in nurturing, education, and PTSD treatment options. Programs like Hidden Heroes® from Elizabeth Dole Foundation and Warrior Care Network® from Wounded Warrior Project® have extended the family’s network of support.

Who Are Hidden Helpers?

According to WWP’s annual warrior survey, 4% of warriors served by WWP list a child as primary caregiver. The WWP data does not define the child’s age. Data from a recent Elizabeth Dole Foundation study conducted in partnership with WWP suggest there are approximately 2.3 million Hidden Helpers: children living with an injured veteran parent or guardian in the U.S. There is still much to learn about the impact of caregiving on this population and the long-term repercussions on military and veteran families.

When children take on caregiving roles, the lines of responsibility can be blurred. While their role may appear less involved than that of an adult caregiver, the mental burden and challenges are no less important or life changing.

For children with a wounded parent or guardian, caregiving can be an additional difference from their civilian peers, just like the frequent moves inherent in active-duty family life. These differences can contribute to children feeling isolated and facing challenges building positive connections with peers.

“Kris and his siblings grew up living the active-duty military life,” Liz said. “By the time Kris was 10 or 11 years old, he had already changed schools six or seven times.”

Even though the moves were positive and the Rotenberry children learned to enjoy making new friends and seeing new places, frequent changes in school curricula, rules, and general atmosphere pose additional challenges. The family landed in Baltimore, Maryland, where they’ve remained since honorably leaving the military. Kris was 7 years old when his dad returned from his last deployment. Before he turned 8, he had absorbed some of his dad’s behavior and PTSD signs.

“Kris adopted some of the same symptoms his dad displayed,” Liz said. He had headaches that mirrored his dad’s, tended to isolate, and questioned why he had to go to school when his dad got to stay home. It happened gradually, but Kris and his siblings started to display moments of hypervigilance and anxiety at home and at school.

“When my dad came home, I remember he looked about the same, and he hugged me all the same,” Kris said. “Eventually, I started to realize he wasn’t quite the same.” At that young age, he remembers thinking that maybe “dad didn’t want to play with us, and he didn’t like to joke around.”

The 7-year-old version of Kris attributed his dad’s changes to “being tired or maybe he was sick.” He noticed his dad spent more time in his room and slept more than before.

“It took a while for me to realize that he wasn’t the same,” Kris said. “I had no clue what my dad was going through at the time. All I knew was that he went away for a long time, and he came back from his job. After a while, I started to do what he was doing. I, too, spent more time in my room.”

Secondary PTSD in Youth Caregivers is Real

Family members of veterans managing PTSD can experience secondary trauma symptoms — or indirect trauma — very similar to what warriors face: anxiety, depression, irritation, and social isolation.

According to WWP’s mental health team, if a warrior copes with PTSD triggers through avoidance, family members can learn the same habits, isolating themselves in life as well.

That’s why WWP staff works to increase awareness and bring attention to, not only warriors managing PTSD, but also family members facing secondary trauma.

Before he understood what PTSD was, Kris would hold back his siblings from greeting their dad effusively at the door and potentially overwhelming him – in an attempt to evade a trigger. His mom took notice of how Kris was becoming a buffer for the family and reached out for help.

“We sought out mental health,” Liz said. She found a Johns Hopkins-Kennedy Krieger program tailored to military families. Kris and his siblings had the opportunity to talk to counselors who either served or understood the military. Together, the siblings started to build an understanding of their own mental well-being.

That understanding has empowered Kris to do well in school, cultivate friendships with peers, and feel at ease among adults as well. These days, Kris enjoys marine biology class and also learning a trade from adult mentors at a local mechanic shop where he works. His supervisor knows the family and gives Kris room to balance work, school, and time with his family.

Kris’ viewpoint on his dad and veterans’ challenges has matured and expanded.

“With me getting older, my dad and I can talk as friends, and we have developed a bond,” Kris said. “I’m glad to see my dad getting help from Warrior Care Network and be able to go all the way to California for some of the best help available. Things have been progressively getting better for him and for me.”

As Kris thinks of life ahead of him, maybe a career as a mechanic or a welder, opening his own business, and perhaps even traveling a bit, he also reflects on how far he’s come and what he would say to his younger self.

“I would say that it gets easier,” Kris said, quickly and wisely correcting himself while calling attention to how he’s learned to positively adapt over the years: “I mean, it doesn’t get easier, but you get used to it. You learn how to deal with it. There are ups and downs – you just got to stick with it. I wouldn’t change anything I’ve been through because of where I am today. I would just tell my younger self, ‘Don’t question things; just do your best.’”

To learn more about how Hidden Heroes supports military caregivers and their families, visit hiddenheroes.org.

To learn more about how WWP helps warriors and families grow together through physical wellness, career counseling, mental health, and PTSD treatment options, and PTSD caregiver support, visit www.woundedwarriorproject.org/programs.

Contact: Raquel Rivas – Public Relations, rrivas@woundedwarriorproject.org, 904.426.9783

About Wounded Warrior Project

Since 2003, Wounded Warrior Project® (WWP) has been meeting the growing needs of warriors, their families, and caregivers — helping them achieve their highest ambition. Learn more.