Through the Perilous Fight: Marine Corps Veteran Unearths Family History of Freedom Fighting

Marine veteran Taniki Richard was born and raised in the United States by Trinidadian parents. She remembers growing up surrounded by West Indian culture. The aroma of Trinidadian curry, the sounds of her dad’s steel drum, and the melody of her parents’ Trinidadian stories and lullabies enriched her childhood.

“When I was growing up, our home was like being in Trinidad,” Taniki said. “I was Americanized in the public schools. Once I opened the front door, I left Trinidad and went to America.”

Taniki enlisted in the U.S. Marines out of high school in California and proudly served her country — the country that welcomed her parents from Trinidad years before. She thought of herself as a Trinidadian-American, born of parents who migrated here from Trinidad before her birth.

Taniki’s parents taught her that “we’re all of one heart,” and she found it easy to get along with Marine brothers and sisters from diverse backgrounds, whether they had longer histories on American soil, or thought of themselves as “newer” Americans, as she did.

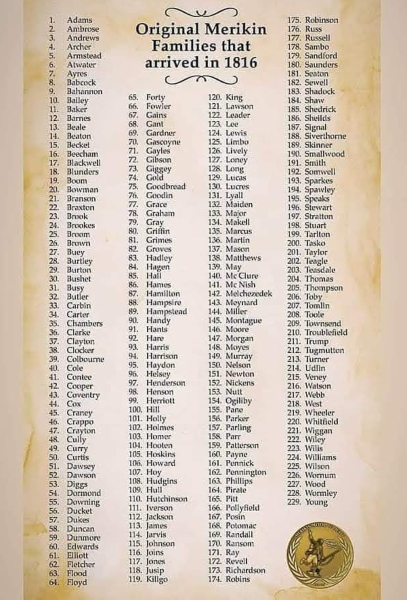

She thought of herself as a new American until she learned about her connection to free African Americans known as “Merikins” in Trinidad. About 800 people, most of whom were members of the British Colonial Marines, were relocated from the U.S. and Canada to Trinidad starting in 1815. Among them was Taniki’s great-great-great-grandfather who had been enslaved in Georgia and fought in the War of 1812 on the British side in exchange for freedom.

Taniki’s self-image as a new American is evolving as she unearths her father’s roots in the U.S., dating back to the 1790s. It turns out Taniki has deeper roots in the United States than she once thought. With help from her father’s sister, Victoria Simon-Holas, she is uncovering her family’s rich history one document at a time.

A birth certificate from a great-grandmother, a reparations claim from a Georgia planter, and historical records all point to a yet unnamed ancestor (one of the enslaved people on the planter’s claim). Victoria and Taniki are searching for the name of Augustus Cooper’s father. Augustus was Taniki’s great-great-grandfather and the first Trinidadian-born ancestor who inherited land in one of the areas where the Merikins settled.

“They knew they were not slaves.”

Although she does not know all the details yet, Taniki nor her ancestor had easy choices. But Taniki cherishes the idea that her ancestor’s decision paved the way for her to serve America by choice.

“I thought of my joining the Marines as getting me away from the wars of the ghetto and thrusting me into the wars of Iraq,” Taniki recalled. Both of her parents served in the U.S. Army. Taniki’s enlistment coincided with the 9/11 attacks, which gave a different tone and purpose to her service.

But through the hardships of war and the heartbreaks of transitioning to civilian life, what stays with Taniki is that her life has been blessed with choices.

“I’m humbled to know that because of my ancestors, I had the choice to sign up and fight,” Taniki said. “I chose to volunteer to lay down my life for others’ freedom, and my ancestors allowed me that grace. A lot of people don’t have that choice. My ancestors certainly didn’t have many choices in the early 1800s in a plantation system, and yet they fought. That’s the deepest part for me, they knew they were not slaves.”

Taniki’s ancestor had to choose between the uncertainty of life as an enslaved man — where a master would decide his fate and that of his family — or a vague offer of freedom and land after serving alongside the British. He didn’t know if he would survive the war, or if the British would make good on their promise.

By taking a big leap and sailing away with the British Colonial Marines, Taniki’s great-great-great-grandfather was granted freedom, land in Trinidad, and the right to pass on that freedom and land to his descendants. This last point is often overlooked by those who might question the motives of soldiers who fought with the British: under plantation slavery, enslaved people had little chance of escaping and little hope of ever improving the fate of their children and grandchildren.

Although Taniki stops short of drawing parallels between her life and the life of her ancestors, it’s hard to ignore the themes of service and sacrifice that repeat through this timeless storyline. Her great-great-great-grandfather wanted a better life for future generations and was willing to put his life on the line. Taniki chose to fight for freedom for her fellow Americans and for the liberation of people in a faraway land. When Taniki found Wounded Warrior Project® (WWP), she discovered new avenues to help others as a veteran and as a civilian. Taniki’s family story shows how every generation has been invested in a legacy of freedom.

How the British Colonial Marines Became the Merikins in Trinidad

The British had courted African American soldiers (free and enslaved) since the Revolutionary War. More than two decades later, the British used the same tactics. They recruited faster than the Americans, who were reluctant to arm Black soldiers.

British ships would come into American harbors like Chesapeake Bay, where they would set up camp on Tangier Island and issue invitations to enslaved people in nearby plantations, and to those who ran away and had made it to the area. They also did this in the South, coming to Cumberland Island, Georgia.

“The British were provoking rebellion in southern plantations and among Native American populations,” explained Keith Cartwright, University of North Florida professor and author. The American government at the time was focused on pushing the British (and the resistance they were provoking) out of the way to open the path to westward American expansion and growth of cotton plantations in the U.S. South.

The British, on the other hand, were concerned with populating Caribbean colonies with people who would be loyal to the English crown. By bringing free African Americans to Trinidad, they were making one of their Caribbean territories more British and less likely to be influenced by surrounding French and Spanish creoles, Cartwright explained.

The new settlers made it to Trinidad in separate voyages between 1815 and 1816. Back in the U.S., planters claimed damages by itemizing each “runaway slave” to receive reparations from the British. Meanwhile, the new inhabitants had to contend with 16 acres of virgin forest to clear, a small provision of food the first year, and seeds to plant crops on their new land.

One of those pioneers was Taniki’s great-great-great-grandfather. Records show he passed land to his son Augustus Cooper, who was successful in planting cocoa.

The relocated soldiers organized into companies, much like they did in the military. They retained the discipline and structure that got them through the war. Their legacy still lives on in the names of parishes and streets in present-day Trinidad. Through the years, they retained their Baptist faith and their identity as “Merikins” as they came to be known in their new home.

Hard Times on Cooper Street and Reverse Migration

Although the Merikins became an important part of the economy and heritage of Trinidad, they worked through the same challenges as the rest of the population, which included descendants of South Asians and Africans who came in waves as indentured servants and laborers.

The standard of living allowed for comfortable housing and broad educational opportunities that a service- and tourism-based economy could no longer support by the 1980s. College-educated Trinidadians began migrating to England, Canada, and the U.S. Taniki’s parents and Aunt Victoria were part of this migration, known as the “Brain Drain” in Trinidad and other islands.

“There was a literacy rate of almost 99%, but few jobs available. We were leaving Trinidad for economic reasons,” said Taniki’s aunt, Victoria Simon-Holas.

Victoria’s dad had left Trinidad to work for Hess Oil Company in St. Croix, so she was no stranger to economic migration. She, too, moved to the U.S. when she found an opportunity and earned advanced degrees and certification as a radiologic technologist.

Before she knew it, 30 years had gone by. Victoria retired and made time to pursue genealogy, an interest she had since an older aunt told her about the family’s connections to the Merikins.

“I didn’t know that much about American history or the history of Black people in the United States,” Victoria said. “I learned as I researched my own family origins.”

Taniki’s Turn at Legacy-Making

Taniki was still dealing with the after-effects of war when her Aunt Victoria was learning about the family’s origins. Taniki’s Marine combat unit was deployed to Iraq in 2007-2008. She worked in aviation electronics, “making sure the planes stayed in the air.” She faced PTSD symptoms when she returned to the states and eventually had a breakdown in 2011. That led her to find WWP.

Her healing process included meeting other veterans, participating in mental health workshops, and beginning and a new chapter as a veteran advocate and motivational speaker.

“Wounded Warrior Project opened me up to feeling and thinking differently about who I am as a veteran, and that confidence spilled over into my relationships, especially my kids,” Taniki said. “They started feeling comfortable about talking to me about how they felt about my PTSD and what was affecting them.”

Sharing her veteran story with others helped inspire her to find new purpose. In the last few years, Taniki has been busy advocating for all veterans, especially women veterans, starting a new enterprise, and a podcast/radio show. She felt she already had a rich heritage and cherished her parents’ Trinidadian ways, so researching her roots was not a project — until Aunt Victoria’s journey of rediscovery shifted her perspective.

“It can never be wrong to reach back into history to find out, even if that history is controversial,” Taniki said. “Our ancestors were fighting for something higher. This is why now I’m able to defend my country. Because they fought to provide that choice.

“My ancestors were enslaved and free men. I fight as a free woman. No one can tell me not to lay my life for my country — I did it by choice. There’s a lot at stake even today and there’s much that still needs to be reformed. Do we learn from our ancestors or do we continue to perpetuate the same cycle of oppression? We want to know so that if there’s ever a time when we need to rise again and fight for freedom, we will know why — and my children will know why even after I’m gone.”

The journey is just beginning for Taniki and her family. “To think that I’m descended from people who fought in the very first war after the United States of America became a country, regardless of what side they fought on — I can only imagine how deep and rich my history is,” Taniki said. “Some people don’t want to know, but I believe that knowing does make a difference in shaping your mind about who you are.”

Learn more about Black soldiers and sailors who settled in Trinidad after the War of 1812.

View the documentary, The Merikins: America, Canada and Trinidad's Forgotten History.

About Wounded Warrior Project

Since 2003, Wounded Warrior Project® (WWP) has been meeting the growing needs of warriors, their families, and caregivers – helping them achieve their highest ambition. Learn more.

SOURCES:

Cartrwright, Keith, Sacral Grooves, Limbo Gateways: Travels in Deep Southern Time, Circum-Caribbean Space, and Afro-Creole Authority. (Georgia: 2013)

Franklin, John Hope, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans. (Durham: McGraw Hill, 1947-1988, Sixth Edition).

Salter, Krewasky A., Combat Multipliers: African American Soldiers in Four Wars. (Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press, Fort Leavenworth, 2003).

Weiss, John McNish, The Merikens: Free Black American Settlers in Trinidad 1815-1816. (London: McNish & Weiss, 2002).

Wilson, Joseph T., The Black Phalanx: A History of the Negro Soldiers of the United States in the Wars of 1775-1812, 1861-1865. (New York, 1887).