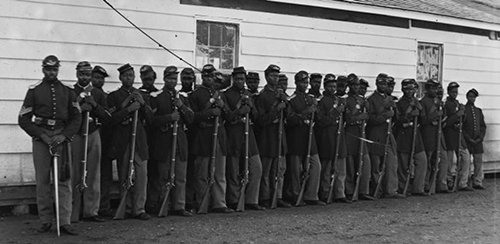

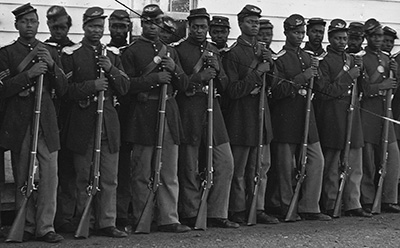

Remembering the Significant Role of the U.S. Colored Troops in America’s History

Most people know the Civil War as a battle between the Union and the Confederacy, or the North vs. South. As we recognize this war, it’s important to also remember and honor the critical role Black soldiers and the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) played in the Union’s victory and preservation of the United States of America.

While not officially allowed to serve in the military at the start of the war, many African Americans volunteered to fight for the Union in all-Black volunteer regiments, and did so with little federal support. After much debate, Lincoln officially allowed Black men to join combat roles in Union military forces in 1863 with the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, although many had already been fighting for Union forces throughout the South after the passage of the 2nd Confiscation Act and Militia Act in 1862. Despite lower wages, poorer living conditions, less access to weapons, and much greater risks if captured, the number of U.S. Colored Troops grew throughout the Civil War, helping to deliver victory for the Union.

Lincoln acknowledged this invaluable service and sacrifice, saying, “Without the military help of the Black freedmen, the war against the south could not have been won.”

Sam Collins, historian and co-chair of the Juneteenth Legacy Project, detailed the often-unrecognized contribution that could only have been made by Black service members and volunteers during the Civil War.

“The North could not have won if not for the Black troops – the United States Colored Troops – because in addition to additional manpower, many of them were former slaves who had important intel,” Collins said. “What is often forgotten is that those runaway slaves knew the Southern territory and landscape. So not only did they take their physical bodies when they ran away, hurting the labor force of the Southern plantations, they also took intel with them. They knew where the creeks were; they knew where you could cross; they knew where [the Confederacy] was storing guns and supplies. So, they would have been able to share that information with Union officers.”

This vital contribution was proven early on in the Civil War during daring raids behind enemy lines along the St. Marys River near the Florida-Georgia border by the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Regiment. A previous raid at that location by all-White Union troops had failed, but unit commander Col. T.W. Higginson credited USCT unit’s success to the local knowledge of the Black freedmen in his ranks. “No officer in this regiment now doubts that the key to the successful prosecution of this war lies in the unlimited employment of Black troops,” Higginson reportedly said.

From 1861 to the end of the Civil War in 1865, approximately 186,000 Black soldiers served in the Union Army and 38,000 were killed in action. More than 94,000 were former slaves from the South. The USCT made up 10% of the Union Army by the end of the Civil War, which couldn’t have been won without their contribution.

Did You Know?

Fight for Equal Pay: According to U.S. government archives, in June 1864, Private Sylvester Ray of the 2nd U.S. Colored Cavalry refused to accept pay that was less than white soldiers and was recommended for trial because of his stand for equal pay. Ray refused to accept the $7 per month pay, while white soldiers made $13 a month. Shortly thereafter, Congress granted equal pay to U.S. Colored Troops and made the decision retroactive to Jan. 1, 1864.

Medals of Honor: There were 16 Medals of Honor awarded to African Americans in the Civil War, with the first going to Sgt. William Carney. Sgt. Carney was born in Norfolk, Virginia, as a slave, but his family was granted freedom and moved to Massachusetts. Carney was hailed for his actions at Fort Wagner, where he protected the U.S. flag from touching the ground, despite being seriously injured. His actions were also credited with the Union’s victory at Fort Wagner.

Added Dangers: Confederate policy was to not recognize African Americans as lawful combatants, making the danger to USCT regiments more significant. Black service members faced re-enslavement or execution if captured by Confederate troops and could not be exchanged as prisoners of war in any circumstance. Captured USCT soldiers who were not executed, were interned indefinitely at prison camps where the mortality rate was near 50%.

Frederick Douglass Factor: Famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass encouraged President Lincoln to allow African Americans to join the fight against slavery in the Union Army. Douglass famously stated, “Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.” After the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, Douglass worked diligently to recruit African Americans to sign up to fight for the Union during the war. Douglass’ own sons, Charles and Lewis, signed up to serve and were part of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, which would be featured in the 1989 award-winning film Glory.

Taking Command: While African Americans were allowed to volunteer for military service per Lincoln’s order in 1962, and be recruited for service after the Emancipation Proclamation, they weren’t allowed to serve as officers or lead troops in combat. The enlisted Black soldiers were often given the most arduous – and often most dangerous – tasks and answered to white officers who were placed in command positions. In 1877, Army 2nd Lt. Henry Ossian Flipper became the first African American to be commissioned in the U.S. military, and the first Black graduate from the U.S. Military Academy. He was also the first Black officer to command African American troops when he was put in charge of Troop A, 10th Calvary Regiment, also known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

Memorials and Monuments

There are many memorials and monuments across the country honoring the U.S. Colored Troops and their service to our nation. Here are just a few of the places where you can see tributes and learn more about some of these heroic service members.

Washington, DC: The national African American Civil War Memorial honors the U.S. Colored Troops and the role they played in the Civil War. A memorial wall boasts 209,145 names of USCT members who fought during the Civil War. There is also a bronze statue and museum onsite that honors African Americans who fought for the Union in the Civil War.

Franklin, Tennessee: The bronze “March to Freedom” statue, unveiled in October 2021, shows a USCT soldier holding a rifle across his leg, with his foot on top of a tree stump and broken shackles beneath his feet. It sits in front of the courthouse downtown right across the street from a Confederate monument.

Clarksville, Tennessee: The life-size bronze statue and granite monument located at the Fort Defiance Civil War Park & Interpretive Center stands 9 feet tall and was unveiled in June 2022. Clarksville served as a recruitment center for escaped slaves who joined the Union Army during the Civil War.

Lexington Park, Maryland: The United States Colored Troops Memorial Statue, which was dedicated in 2012, honors the more than 700 Black soldiers and sailors from St. Mary’s County who fought for the Union in the Civil War.

Wilmington, North Carolina: The “Boundless” USCT memorial displays 11 life-size bronze statues representing the three ranks of the U.S. Colored Troops and is the centerpiece of U.S. Colored Troops Park. The faces of USCT descendants, USCT re-enactors, African American veterans from the area, and Black leaders in the community were used to make the castes for the faces of the 11 statues.

Fort Myers, Florida: The large bronze statue depicts a sergeant in the USCT 2nd Regiment. Behind him is a wall with two granite plaques: one that details the contribution made by the 2nd Regiment in the Civil War and the other featuring a poem “In Freedom Cover Me,” written by the monument sculptor D.J. Wilkins.

Vicksburg, Mississippi: The monument commemorates the 1st and 3rd Mississippi Infantry Regiments and features bronze statues of a Black Union soldier and a civilian fieldhand helping a wounded USCT soldier. The statues sit on a large black granite base. The monument is located in Vicksburg National Military Park.

Contact: — Paris Moulden, Public Relations, pmoulden@woundedwarriorproject.org, 904.570.7910

About Wounded Warrior Project

Since 2003, Wounded Warrior Project® (WWP) has been meeting the growing needs of warriors, their families, and caregivers — helping them achieve their highest ambition. Learn more.