PTSD: A Warrior’s Life Before & After

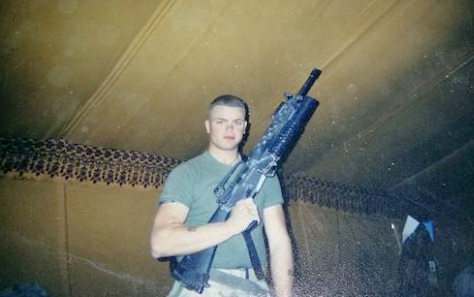

Matthew Barnes traces his problems back to his Iraqi deployment during the 2003 ground invasion. Less than six months after joining the Marines, Matthew — a brand new lance corporal attached to an infantry unit — was deployed as an infantry machine gunner and on patrol with his unit in Iraq. Back home, Matthew was an outgoing country boy who enjoyed going off-roading and mountain climbing. On August 29, 2003, that all changed.

It happened without warning — a car bomb detonated outside the Imam Ali Mosque in Najaf, killing nearly 100 people and injuring more than 500, only blocks away from Matthew’s location. U.S. news reports called it the deadliest attack since the Iraq war ended. The blast haunted Matthew for the rest of his military career, and continued to snowball in his civilian life.

In combat situations, the mind reacts instinctively, collecting and sorting memories that can be excruciatingly difficult for a warrior to endure during the inevitable recall process. Therefore, the mind’s “filing system” and unintentional memory recall can elicit great harm to a combat veteran’s mental health and well-being. This reaction has been called many things.

Today, it is called post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Matthew, unknowingly, fell deep in its trenches.

PTSD is a condition that can develop after a person is exposed to a traumatic event. Symptoms can include disturbing thoughts, feelings, or dreams related to the event; mental or physical distress; difficulty sleeping; and changes in how a person thinks and feels. Veterans experiencing PTSD may have triggers, which are linked to situational or emotional experiences and memories. For instance, soldiers with PTSD may hear the sound of popcorn popping or fireworks exploding and recall an improvised explosive device attack. Or a random experience of anger, sadness, or anxiety could trigger veterans to relive the experience and emotion of losing a friend in combat.

PTSD is an invisible wound that can dismantle a warrior’s life unless they have the tools and treatment needed to succeed in recovery. Many warriors are concerned with the stigma associated with injuries that are not visible. They either never get connected with the treatment they need, or they go another route to deal with their issues.

Matthew chose to self-medicate.

“I didn’t have to worry about having nightmares because I wasn’t sleeping,” said Matthew, who — within two years of the explosion — failed a drug screening and was forced out of the military.

Losing something that was so deeply embedded in his life was the jolt Matthew needed to get clean. And while he has maintained that sobriety since 2015, Matthew’s struggle continued. From employment to relationships, PTSD had a firm hold on Matthew’s life.

“I didn’t like new people, and I didn’t like crowds,” Matthew said. “I began to live as a hermit when I wasn’t at work. I never went anywhere or did anything. Then my wife noticed my constant anger and frustration. She put the pieces together. I had been dealing with PTSD, but I didn’t even know it.”

After reaching out for medical help, Matthew was finally diagnosed with PTSD in April 2016.

That’s when Matthew discovered Wounded Warrior Project® (WWP). The veterans charity partners with four academic medical centers and VA in its Warrior Care Network® to provide lifesaving clinical mental health care. The partnership ensures injured veterans dealing with PTSD, traumatic brain injuries, or combat stress receive the best mental health care regardless of their location. Thanks to the support of generous donors, the services are free to warriors. The brave servicemen and women deserve no less, having already paid their dues on the battlefield.

Shortly after registering, Matthew was enrolled in mental health services at Emory Healthcare Veterans Program and introduced to prolonged exposure (PE) therapy, administered daily by a professional therapist. According to the VA, PE therapy is one of the most effective treatments for PTSD. It repeatedly exposes the patient to his or her distressful thoughts, feelings, and situations directly related to the traumatic event. By confronting high-stress triggers linked to PTSD — instead of avoiding them — patients can learn about their PTSD reactions, develop skills to manage stress, practice control techniques in real-world situations, and talk through the traumatic event to gain more control of the associated thoughts and feelings.

Recounting and discussing the circumstances around the 2003 Imam Ali Mosque bombing left Matthew in tears. “It was harder than going through boot camp,” said Matthew, who during his PE therapy sessions relived his traumatic experience in detail: thoughts, emotions, sights, smells, sounds, tastes, and skin sensations. These were memories he previously avoided at all costs. Matthew allowed doctors to probe his memory daily, then he returned to his room and listened to the recorded sessions on his own.

“You walk through the event; then you walk through it again — over and over,” Matthew said. “It’s like having a cluttered closet that you didn’t want to deal with. Prolonged exposure therapy removes everything from the closet, then — after taking a nice, hard look at each item — it identifies the correct place they belong.” It’s an exhausting and stressful process, but Matthew said it started helping.

“The first night or two, my PTSD was reinforced, and I couldn’t sleep,” Matthew recalled. “It forced me to deal with my issues. But by the end of the third day, I started to get through the event without any anxiety.” It was a change he didn’t think was possible. Instead of learning to merely cope with his new normal, Matthew credits Warrior Care Network and Emory staff with helping him get closer to being the man he was before his deployment.

“I feel like my old self,” Matthew said. “I’m getting out of the house as much as possible and getting back into the hobbies I haven’t enjoyed in a very long time. My family and employer have noticed a significant change.”

Warrior Care Network includes the Veterans Program at Emory Healthcare; Home Base, a Red Sox Foundation and Massachusetts General Hospital program; Operation Mend at UCLA Health; and Road Home at Rush University Medical Center. The program delivers more than 70 hours of clinical care to each veteran in 2- to 3-week intensive outpatient programs. That is more clinical care than most outpatients would see in a year.

“This program gave me my life back,” Matthew said.

Learn more about how warriors can find PTSD treatment that empowers them to move forward in their recoveries.

About Wounded Warrior Project

Since 2003, Wounded Warrior Project® (WWP) has been meeting the growing needs of warriors, their families, and caregivers — helping them achieve their highest ambition. Learn more.