Legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen: The First African American Military Pilots

“They have a saying that excellence is the antidote to prejudice; so once you show you can do it, some of the barriers will come down.” – Dr. Roscoe Brown, Tuskegee Airman

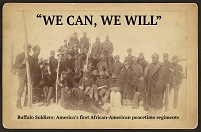

By the time the United States entered World War II, African Americans had fought in every American war since the Revolutionary War. In each era, Black troops showed courage and strength on the battlefield. Yet while they served their country, they also faced unfair treatment at home. Segregation and discrimination made life hard and limited opportunities in the military.

As the role of Black soldiers grew, so did their demand for equal training and respect. During World War II, many African American service members wanted to join the Army Air Corps and learn to fly. Their push for change helped create a new chapter in history: the Tuskegee Airmen — the first African American military pilots and their support crews.

Who Were the Tuskegee Airmen?

The Tuskegee Airmen are known as the first African American military pilots in U.S. history. They trained in a segregated program during World War II at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Despite facing discrimination and doubt, their service helped challenge unequal treatment in the military and became a symbol of progress in U.S. aviation and civil rights.

Tuskegee Airmen Col. Benjamin O. Davis, and Edward C. Gleed, wearing flight gear, look to the sky at an air base in Ramitelli, Italy. (Library of Congress photo)

Voices Unite for Change: What Led to the Creation of the Tuskegee Airmen Program

When World War II began, the nation was still divided by race. Jim Crow laws in many Southern states enforced segregation. The U.S. Supreme Court’s “separate but equal” ruling from Plessy v. Ferguson allowed schools, transportation, and public places to remain divided by race. This reality hurt the morale of Black service members. It also limited their chances for training and promotion.

Segregation and Barriers in the U.S. Military

The military had its own barriers. In 1925, the U.S. Army War College prepared a report titled “The Use of Negro Manpower in War.” The report wrongly claimed that Black troops lacked the moral strength and intellectual ability for skilled jobs and higher ranks. This unfair judgment restricted opportunities for Black service members and slowed the path toward desegregation.

Civil rights groups pushed back. In 1939, the NAACP launched public campaigns to end segregation in the armed forces. Leaders argued that Black men and women deserved equal chances to train, serve, and lead. There was also a strong push to admit Black cadets into the Army Air Corps flight programs.

Learn about the first Black fighter pilot

Tuskegee Airmen Marcellus G. Smith and Roscoe C. Brown work on a plane in Ramitelli, Italy, in March 1945. (Library of Congress photo)

Legal Action Opens the Door to Training Opportunities

In January 1941, a major legal step moved things forward. Yancey Williams, a civilian pilot and student at Howard University, filed a lawsuit in Washington, DC. He had applied to become a flying cadet but was turned away because no training units accepted “colored applicants.”

As pressure from civil rights groups and the public grew, the Army Air Corps responded. It created a segregated training program for Black pilots and support crews at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. While this was not full integration, it was a breakthrough that opened the door for African American airmen.

Training Begins at Tuskegee: Overcoming Doubt and Discrimination

Training for the Tuskegee Airmen started in 1941 with an inaugural class of 13 men. They trained for flight at Moton Field, the Army airfield near Tuskegee, and studied at Tuskegee University. The program was demanding. Of the first class, five completed the rigorous course. But the program did not stop there. From 1941 to 1946, about 1,000 African American pilots graduated from the Tuskegee training program. Many more served as navigators, bombardiers, mechanics, and support staff.

Charles “Chief” Anderson’s Leadership

A dedicated instructor helped make this possible. Charles Alfred “Chief” Anderson led the training program and became known as the Father of Black Aviation. His skill and calm leadership gave trainees confidence.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s Historic Flight: 'Well, You Can Fly All Right'

Tuskegee airmen leaving the parachute room in Ramitelli, Italy, in 1945. (Library of Congress photo)

Early in the program, the Tuskegee Airmen gained national attention when First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the facilities. She spoke with Chief Anderson about the widespread belief that Black troops were not fit for flight training. Anderson invited her to join him on a demonstration flight. After a 40-minute flight, she declared, “Well, you can fly all right.” A photograph of the First Lady flying with Anderson appeared in newspapers across the country and helped change minds. The message was clear: the Tuskegee Airmen were ready and able.

Red Tails Go to War: How Did the Tuskegee Airmen Contribute to World War II?

As the program grew, Tuskegee-trained pilots and crews formed four fighter squadrons: the 99th, 100th, 301st, and 302nd. Together, these squadrons made up the 332nd Fighter Group. Their aircraft had red-painted noses and tails, which stood out in the sky. This bold look earned them the nickname “Red Tails.” In time, they became known to bomber crews and enemy pilots alike.

WWII Missions and Military Achievements

Some of the first cadets at the Basic and Advanced Flying School for Negro Air Corps Cadets line up for inspection on Jan. 23, 1942, in Tuskegee, Alabama. (Library of Congress photo)

The 99th Pursuit Squadron was the first to go overseas. They flew to North Africa under the command of Capt. Benjamin O. Davis Jr., who later became the first Black general in the U.S. Air Force. On their first combat mission, they attacked a volcanic island in the Mediterranean. During the fight, more than 11,000 Italian soldiers and 78 German soldiers surrendered. The Red Tails displayed bravery in mission after mission and earned three Distinguished Unit Citations for their service.

By 1944, the rest of the 332nd Fighter Group joined the war in Europe. Their main job was to escort bomber planes during long raids over enemy territory. The pilots followed strict orders to stay with the bombers and not break formation to chase enemy aircraft. This tactic meant fewer pilots became “aces,” a title given to a fighter who shoots down at least five enemy planes. But it also saved lives. The Red Tails lost fewer bombers during escort missions, which was a major achievement. Soon, bomber crews began to ask for the “Red Tail Angels,” trusting the Tuskegee Airmen to protect them during dangerous missions.

The Tuskegee Airmen’s Role in Military Desegregation

The numbers tell the story of their impact. By the end of World War II, the Tuskegee Airmen had flown about 1,500 missions. They earned many awards and citations for their courage and skill, including Distinguished Flying Crosses and Purple Hearts. Their service became part of the push for equality in the military, leading to President Harry Truman signing Executive Order 9981 in 1948, which desegregated the U.S. armed forces. This order was a landmark in American military and civil rights history.

Lasting Legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen

“You grow up feeling a love for your country in spite of its imperfections. You’re happy and proud to be an American who just happens to have a different pigmentation, a different skin color.” – Herbert Carter, Tuskegee Airman

Decades have passed since a small group of Black soldiers gathered in Alabama to do what many said could not be done. The legend of the Tuskegee Airmen remains a relevant and significant chapter in the nation’s history. Their story has been immortalized many times, including in two popular films: The Tuskegee Airmen, starring Laurence Fishburne (1995), and George Lucas’ Red Tails (2012).

In March of 2007, President George W. Bush presented 300 surviving Tuskegee Airmen and family members with Congressional Gold Medals – the top civilian award given by Congress.

Following in Their Footsteps

Dr. Tyshawn Jenkins had veterans in his family, but he hadn’t really given joining the military much thought. That changed during his senior year of high school, when Tuskegee Airman George Watson Sr. visited his class. Hearing Watson speak about his experiences — and the sacrifices he made in the face of discrimination — left a lasting impression.

Now an Air Force captain, Tyshawn credits that moment with helping to shape his future.

“When I think about the Tuskegee Airman who came to our school, those were some of the things that he embodied upon us … his service, sacrifice, and the experiences he had despite the racial discrimination and things of that nature,” Tyshawn said. “There was a greater purpose, and I think that's always really resonated with me.”

Tyshawn Jenkins wrote the names of Tuskegee Airmen and other Civil Rights change-makers on his sneakers to remind him to keep fighting.

During Tyshawn’s impressive Air Force career, he worked in aircraft fuel maintenance, military intelligence, and public affairs, with the goal of one day becoming an officer. It turned out to be a journey filled with obstacles and barriers.

“I wanted to give up so many times,” Tyshawn said. “When I began to think about why I kept going, I thought about those Tuskegee Airmen and those who came before me.”

In 2020, Tyshawn was commissioned as an Air Force officer.

Tyshawn keeps a coin of the Tuskegee Airmen on his desk as a reminder of that service and greater purpose. He also owns a pair of sneakers honoring the Tuskegee Airmen alongside other Civil Rights pioneers — a personal reminder to keep moving forward, one step at a time.

“They served a country that didn’t always serve them — and that’s something I carry with me,” he said.

For Tyshawn, their legacy comes with a responsibility to inspire those who follow, much like George Watson and the Tuskegee Airmen once did for him.

One of the things he’d like to pass on to future generations of service members is the willingness to ask for — and receive — help.

“We still have that stigma that if you say something about being physically hurt or having those invisible wounds, that you're going to get released from service,” Tyshawn said. “That's where I'm able to share my experience. There are resources like Wounded Warrior Project, and you're able to go there to get the help that you need. You don't have to do it alone, and you can still serve.”

Honoring the Tuskegee Airmen means more than remembering what they endured — it means living out the values they demonstrated. Their courage, commitment, and determination remain a call to action, a reminder that service is not just about answering a moment in time but about carrying a legacy forward.

The story of the Tuskegee Airmen and those who came before is inseparable from progress today. They served with distinction at a time when opportunities — and respect — were not guaranteed.

“Had they given up,” Tyshawn said, “I wouldn’t be where I am.”

Find out how WWP continues to honor and empower those who served.

Contact: Paris Moulden, Public Relations, pmoulden@woundedwarriorproject.org, 904.570.7910

About Wounded Warrior Project

Wounded Warrior Project is our nation’s leading veteran services organization, focused on the total well-being of post-9/11 wounded, ill, or injured veterans. Our programs, advocacy, and awareness efforts help warriors thrive, provide essential lifelines to families and caregivers, and prevent veteran suicides. Learn more about Wounded Warrior Project.